The first exhibition of its kind in the United States, Sharing Images: Renaissance Prints into Maiolica and Bronze, brings together some 90 objects to highlight the impact of Renaissance prints on maiolica and bronze plaquettes. Accompanied by a publication that provides a comprehensive introduction to different aspects of the phenomenon—from the role of 15th-century prints and the rediscovery of classical art to the importance of illustrated books and the artistic exchanges between Italy and northern Europe—Sharing Images will be on view on the ground floor of the West Building from April 1 through August 5, 2018.

“This exhibition provides an unprecedented opportunity to examine the extent and depth of prints, plaquettes, and maiolica in the Gallery’s collection,” said Earl A. Powell III, director, National Gallery of Art. “The visual links between these objects vividly demonstrate that Renaissance prints, produced in large numbers and rapidly diffused, were among the earliest viral images in European art. We are grateful for a grant from the Eugene V. and Clare E. Thaw Charitable Trust, which made it possible to explore the complex and unpredictable connections shared between these works of art.”

“This exhibition provides an unprecedented opportunity to examine the extent and depth of prints, plaquettes, and maiolica in the Gallery’s collection,” said Earl A. Powell III, director, National Gallery of Art. “The visual links between these objects vividly demonstrate that Renaissance prints, produced in large numbers and rapidly diffused, were among the earliest viral images in European art. We are grateful for a grant from the Eugene V. and Clare E. Thaw Charitable Trust, which made it possible to explore the complex and unpredictable connections shared between these works of art.”

Arranged chronologically, this exhibition is inspired by the acquisition of the William A. Clark maiolica collection from the Corcoran Gallery of Art and draws largely on the Gallery’s newly expanded holdings of early Italian prints (founded on the Rosenwald gift and augmented by recent acquisitions), as well as on the world-renowned Kress collection of plaquettes and medals. It traces the metamorphosis that designs by Andrea Mantegna, Antonio del Pollaiuolo, Raphael, Michelangelo, Parmigianino, and Albrecht Dürer, among others, underwent across these different media.

About the Exhibition

Sharing Images tells the story of how printed images were transmitted, transformed, and translated onto ceramics and small bronze reliefs, creating a shared visual canon across artistic media and geographical boundaries. Often acknowledged, but rarely studied in depth, the impact of prints on other media is most visible in Renaissance maiolica (tin-glazed ceramics) and bronze plaquettes.

Fifteenth-century Europe was a place of technological revolution, particularly in the parallel development of printed books and images. These developments transformed the ways in which verbal and visual information could be accessed, with radical implications on cultural, scientific, and artistic production. As easily produced multiples, prints traveled widely. They were frequently copied by artists and craftsmen and were a driving force in the revolution of the arts of the Renaissance.

Small bronze reliefs, known as plaquettes, functioned primarily as refined ornaments or collectibles—a format influenced by ancient carved gems, coins, and statues—first appeared in Rome around 1440. As small, portable objects meant to be handled and privately enjoyed, plaquettes were similar to prints and often produced in or near important printmaking centers, such as Mantua, Bologna, or Venice. On view in the exhibition is Andrea Briosco’s (1470–1532) plaquette Judith with the Head of Holofernes (early 16th century), alongside the print that inspired it, Judith with the Head of Holofernes (c. 1480), by a follower of Andrea Mantegna. Briosco responds to Mantegna’s figural style by reducing it to a three-dimensional handheld object, creating an intimate, tactile encounter with the image. Also on view are three plaquettes by one of the masters of the medium, Moderno (Galeazzo Mondella, 1467–1528): The Flagellation, The Entombment, and Hercules and Antaeus (all dating from the late 15th to early 16th century).

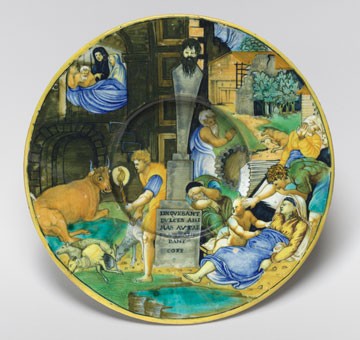

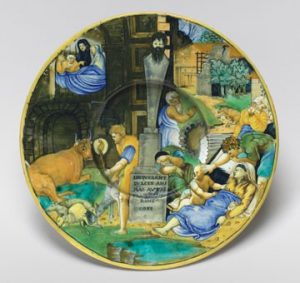

Inspired by the availability of new pigments, glazes, and printed models, ceramics artists developed a style of decoration called istoriato that featured recognizable subjects and narrative episodes from classical and contemporary literature as well as biblical and ancient history. For the first time, pottery painters conceived of the surfaces of plates and vessels as a medium to depict stories in full color and vivid detail. Like prints, istoriato mirrored and visualized the interests and passions of the cultured elite while remaining accessible to a wider market. Painters in the principal cities of istoriato production—Faenza, Urbino, Pesaro, Gubbio—could respond to the most recent developments in contemporary art thanks to the availability of printed images created in major artistic centers.

While artists in the above cities were early adopters of printed material as sources, those in Deruta, with notable exceptions, remained attached to the style and works of local painters such as Pietro Perugino (c. 1450–1523) and Pinturicchio (1454–1513) until the mid-16th century. One such exception, Dish with Hercules and Antaeus (c. 1490–1500)—a spectacular Deruta plate on view in the exhibition—depicts the interlocked bodies of the two subjects dynamically engaged in combat. One of the earliest examples of Umbrian istoriato, the Deruta plate illustrates how quickly artists could respond to Antonio Pollaiuolo’s (1431/2–1498) innovative and dramatic compositions of the male nude body in motion even in relatively more conservative centers.

Exhibition Curator

The exhibition is curated by Jamie Gabbarelli, assistant curator of prints, drawings, and photographs at the Rhode Island School of Design Museum. The exhibition is the culmination of Gabbarelli’s research as the Andrew W. Mellon Postdoctoral Curatorial Fellow in the department of old master prints from 2015 to 2017.

Sharing Images will be on view in the West Building from April 1 through August 5, 2018.